Execution Fascination

Will Social Media and Potential Record Profits Bring Back Public Executions?

Washington, D.C., August 14, 2026 — Double rows of stationary klieg lights shot towering beams skyward, casting enormous shadows on the Truman Balcony, while a dozen more positioned on the South Lawn of the White House swept the sky as if announcing a blockbuster movie premier.

The paying guests, who ponied up $10,000 per ticket, mingled in the sweltering summer heat, sipping specialty “Killer Kocktails” featuring the rebranded (and allegedly watered-down) Trump Victory Vodka and nibbling on tiny, hand-made hors d’Oeuvres with event-inspired names like “Murderers Roe” and “Guilty Pleasures.”

Giant video screens ringing the grassy parcel looped fluttering American flags, scenes of military might and MAGA rallies, and an AI-generated panorama of the soon-to-be five Mount Rushmore presidents—Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt, Lincoln, and Trump—as massive speakers blared a medley of patriot marches, gospel choirs, country stars, and classic rock.

A ripple of excitement coursed through the crowd as Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth “loudly and proudly” announced, “Ladies and gentlemen, honored guests, and fellow patriots, thank you for joining us this historic evening. It is my profound honor to welcome the greatest president in our nation’s glorious history. A man who loves this country more than any man I’ve ever known. A man who says what he’ll do and does what he says. A real man. A fearless leader. Donald J. Trump.”

As the Marine Band—the President’s own—launched into Hail to Chief and President Trump stepped onto the balcony, the crowd erupted. Spontaneous chants of “USA! USA! USA!” and “Trump! Trump! Trump! filled the night sky, echoing off the nearby federal buildings. The President reveled in the moment, his chin jutting and fist pumping. Shielding his eyes, he pointed and gave a thumbs up to pint-sized participants, though it seems unlikely he could identify anyone through the lights’ blinding glare.

As the chorus of praise subsided, a lone female voice shouted out, “We love you!” sparking a new round of cheers and applause. Finally, the new wave of adulation mellowed, and the president spoke.

“Thank you. Thank you very much. I love you, too. (Cheers, Scattered applause.) Welcome to this historic event—an event for JUSTICE and the rule of law in our great country. And it is a great country. We’ve MADE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN! (Cheers, Sustained applause). Because of our movement and the brave, hard-working people in law enforcement, the murderers, rapists, and illegal scum are no longer invading our country. They’re no longer roaming our streets, terrorizing our communities and bringing pain and suffering to millions. We’ve put an end to all that. Now, these horrible animals are the ones suffering. (Cheers, Applause.) They're finally paying the price—in some cases, the ultimate price—for their reign of terror. Big, beautiful detention centers, like Alligator Alcatraz, have been constructed all across the country. They’re bursting at the seams. But we’re going to have to keep building until all the disgusting perverts and MS-13 gang members are captured and put where they belong. We’re going to keep meting out justice to these criminal losers.

As you know, tonight, around the nation and really around the world, honest, God-fearing people like you will have the opportunity to witness what happens to those who commit the most heinous crimes. No more endless litigation through our broken courts. No more stays. No more radical left ACLU lawyers wasting everybody’s time filing useless, last-minute appeals to the Supreme Court.

As it says in the Bible—the greatest book ever written— ‘An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.’ Tonight, we’re doing God’s work! (Cheers, Applause.)

Right before I came out here, I was told everything is set, running perfectly. The low-life murderer had his last meal. He met with his priest. His head and ankle area have been shaved and ‘Old Sparky’ has been tested and is ready to go.

But first, I want to thank Gov. Ron DeSantis of the great state of Florida—my home state, a state I love—and the Florida legislature for changing the law so that cameras can record this historic moment. (Applause.) Thanks also to Warden Dave Maddox of the Apalachee Correctional Institution for his hard work arranging this event. Dave has the necessary witnesses all lined up. I don’t know how he did it, there were so many people who wanted to be there, but Dave did a great job. The executioner who’ll flip the switch to deliver the 2,000 volts of JUSTICE for the victim’s family is standing by and ready to roll. The cameras are in place and the pay-per-view stream is live. (Applause, Cheers.) Millions of people have logged in. Bars all across the country—all around the world, actually—are holding watch parties like ours. I’m told they’re packed! (Cheers, Applause.)

The hundreds of millions of dollars in pay-per-view revenue is far exceeding expectations. Nobody has ever seen anything like it. It’s probably going to be the biggest televised, or streamed, or downloaded, or whatever event in history. It will be bigger than any of the Super Bowls, ever. (Applause.)

Ninety years ago today, in the great state of Kentucky, a vicious animal who raped and murdered an elderly widow was hanged. Thousands of people came to watch him pay for his horrible crime. That was the last time the public had the opportunity to witness a criminal paying the ultimate price. That ends tonight! Tonight we bring back liberty and JUSTICE for all! (Sustained applause and cheers.)

Because of the tremendous deal we made with Fox and AON, your federal government will take half of the revenue generated by this long-overdue event. It’s an amazing deal. Florida will get five per cent to cover expenses, the victim’s family will get five per cent, too, and Fox and AON will split the rest. I don’t know exactly how they’re going to split it. Maybe their CEOs can wrestle for it. Maybe we set up a little ring or maybe a cage match here. I don’t know. Maybe they can do their own live stream. That would be good TV. I’d pay to watch that. (Laughter, a smattering of applause.)

I’m being told I need to wrap this up so we can get on with the show. So, thanks again for coming. Grab another of those fabulous Killer Kocktails and find a good spot so you can watch on one of those big, beautiful screens. The wait is over! The media event of the century is about to begin! Thank you for your attention to this matter. God bless you and God bless the United States.”

Far-Fetched Fantasy?

The idea that President Trump would host a money-making, invitation-only event to watch a live, pay-per-view execution might seem absurd, but given the country’s long, troubling history of “celebratory” public hangings, and Trump’s monetization of the Presidency, the prospect of a revenue-generating “event” is not as preposterous as one might think at first glance. The recent sale of “Alligator Alcatraz” merch and Trump’s announcement that he plans to hold an Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) event for 20,000-25,000 people on the White House lawn as part of his America 250 celebrations suggests he is open to the concept. The possibility that social media would embrace a live execution is even more likely. In fact, three decades ago, we flirted with the idea of televised executions.

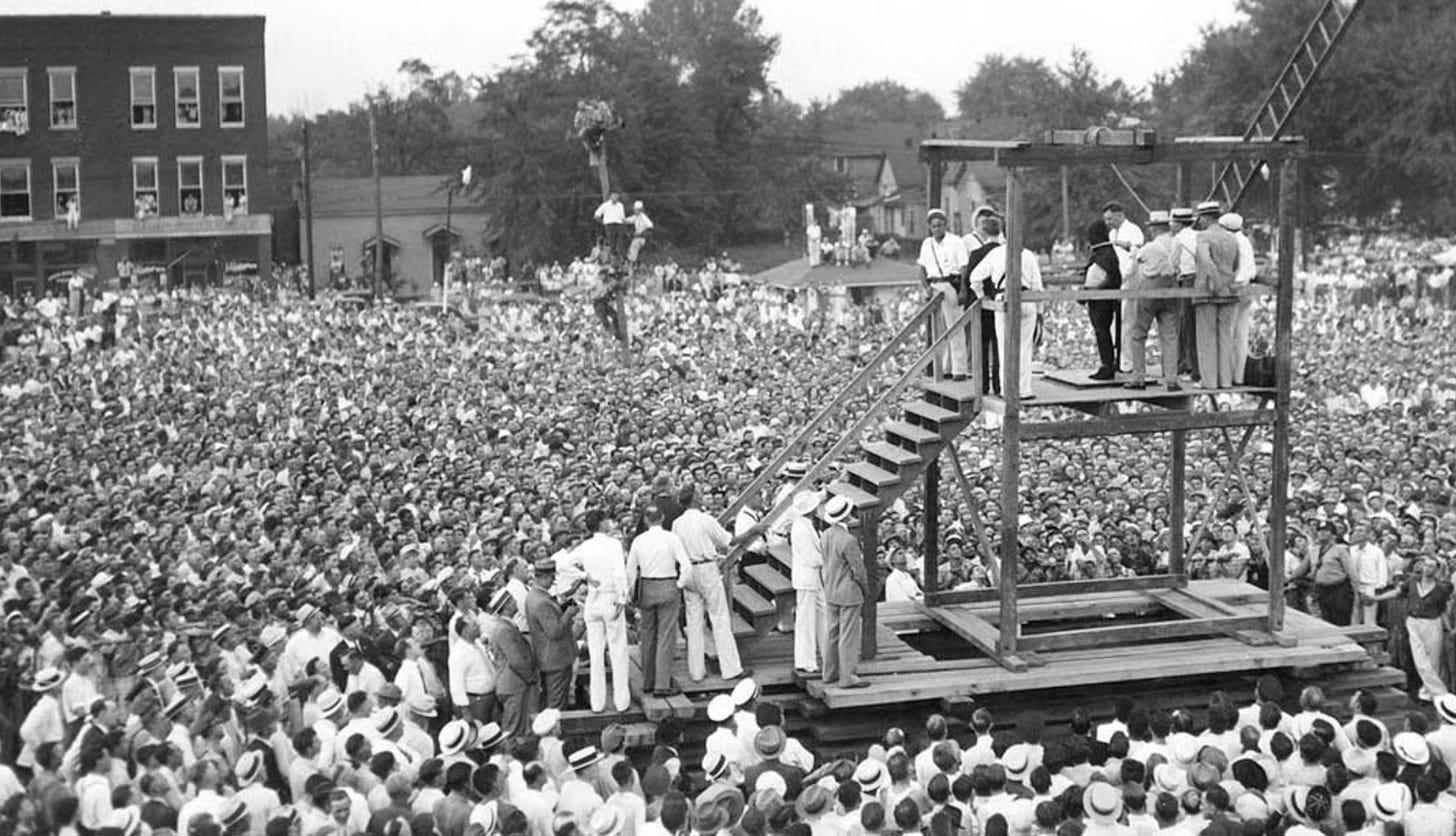

New technologies have always be used to memorialize executions. Photographers and newsreel cameras captured the event on August 14, 1936, when between 10,000 and 20,000 spectators (estimates vary) gathered in Owensboro, Kentucky to witness the last, legal public hanging in the United States. It was the only public execution ever held in Owensboro. Rainey Bethea, a 22-year-old African-American convicted of the rape and murder of 70-year-old widow Lischia Edwards, was hanged.

(Note: The May, 1937 Galena, Missouri hanging of murderer Roscoe “Red” Jackson was also officially considered a public execution, though the hanging was done inside the confines of a stockade. Between 500 and 3,000 townspeople, police, and prison officials witnessed the hanging Again, estimates vary..

Michael Donald, a 19-year-old African-American was lynched in Mobile, Alabama on March 21, 1981. It is believed to be the last lynching in the country. Four KKK members were eventually tried for Donald’s “extrajudicial” hanging. One was convicted and executed in 1997. Two others were sentenced to life in prison, but were paroled after serving 25 and 11 years, respectively. The fourth collapsed in court during his trial. The judge reluctantly declared a mistrial and the accused died of a heart attack before he could be retried.)

Contemporaneous accounts of Bethea’s execution offer wildly different stories of how the massive crowd behaved, though most describe the gathering as “orderly.” Sensationalist press reported members of the crowd rushed the gallows, ripped the black hood from Bethea’s head and tore it up, taking away the pieces as souvenirs of the event, but those stories are suspect. There is widespread agreement that a “carnival” atmosphere permeated the hanging. “Thousands poured into Owensboro during the night, in automobiles, wagons, and on freight trains, to witness the spectacle,” the Cincinnati Enquirer reported. “Many sought position of vantage about the gallows, spotted before daybreak by a bright electric light. There were house parties for out-of-town thrill seekers.”

Local entrepreneurs took advantage of the opportunity. “Vendors shouted their wares for a crowd in a county fair mood— ‘ice cream…hot dogs…get your nice hamburgers…cold soda pop’—everybody seemed in good humor,” the Enquirer said.

A Missouri newspaper reported that the crowed “cheered and yelled as Bethea’s body dropped,” but “was not ill natured or violent” and simply “appeared to be enjoying a ‘hang-man’s holiday.’”

Rainey Bethea, moments before his hanging, August 14, 1936, Owensboro, KY

By some estimates, the crowd more than doubled Owensboro’s population. African-American citizens, fearing a race riot, hid in their homes. A United Press correspondent reported that the only black residents he saw were the bellhops staffing the packed hotels.

The media circus surrounding Bethea’s public execution compelled the state legislature to revise Kentucky law, moving executions, including hangings, out of public view.

The Public’s Long Fascination

The public’s ghoulish fascination with state-sanctioned executions and “extrajudicial” mob lynchings stretches far back in American history. The NAACP estimates that, between 1882 and 1968, 4,743 lynchings occurred in the United States, though it's “impossible to know for certain how many there were because there was no formal tracking” and “many historians believe the the true number is underreported.” Lynchings occurred in almost every state. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice (informally known as the National Lynching Museum) in Montgomery, Alabama, includes 805 hanging steel structures representing each of the U.S. counties where a lynching took place.

Though many of the lynchings were done in the dead of night, some were long, tortuous, well-documented affairs. In the late 19th and early 20th century, lynching postcards were collected, traded, and circulated through the mail. The U.S. Postal Service didn’t ban the practice until 1908. In some instances, spectators gathered their own souvenirs, including body parts cut from lynching victims.

The American people’s interest in legal executions also has a long history. Two decades after Bethea’s public hanging, the widely covered, gas chamber execution of Barbara Graham stirred controversy. Like Bethea, Graham, 31, was convicted (along with two accomplices) of murdering an elderly widow. All three perpetrators were executed in the gas chamber at San Quentin Prison in California on June 3, 1955.

Though Graham had a long criminal history, and never denied that she participated in robbery-gone-wrong murder, her execution sparked debate as the public’s attitude toward capital punishment evolved. Sympathetic editorials raised questions about society’s role in Graham’s illegal activities.

“Yes, Barbara Graham is dead and the story was good for a series of headlines and some of the most brilliant and engrossing news writing seen in many a long day. Everyone read the stories with a thrill of excitement,” a Los Angeles Times editorial said. “But after reading, what? Then come the second thoughts. Was Barbara Graham really guilty, or were you and I guilty, too?

“Barbara Graham never had a chance,” the editorial continued. "At 13 she was put in a reform school, as unmanageable, by her mother. What did she learn there? She learned to be a prostitute, a user of narcotics, a forger and a murderer. They didn’t label the courses by those offensive names, but that is what she learned, because that is what she became.”

Three years after her execution, I Want to Live!, a film loosely based on Graham’s life, was released. Susan Haywood portrayed Graham and won the Academy Award for Best Actress of 1958.

Barbara Graham, entering the gates of San Quentin, the day before her execution.

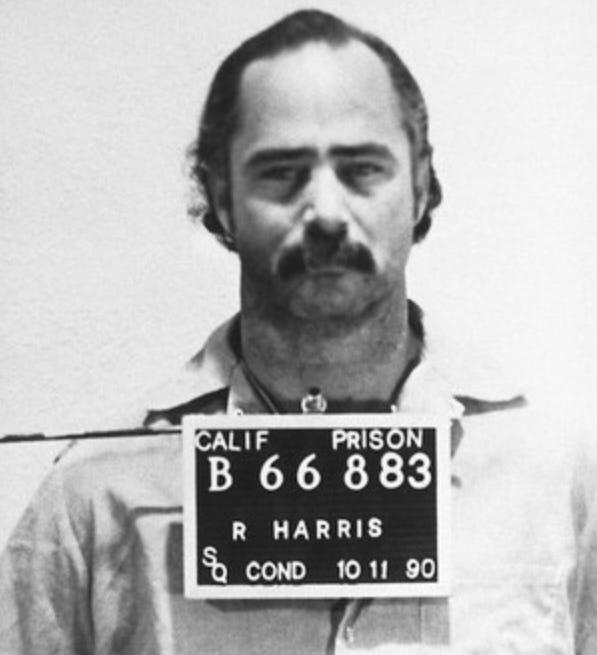

Fast forward 33 years through the decades of debate over the propriety and efficacy of capital punishment. Back in San Quentin, Robert Alton Harris sits on death row awaiting his execution for the 1978 murders of two teenage boys. He would be the first prisoner executed in the state since 1967. Meanwhile, San Francisco public television station, KQED, is in court seeking the right to film and televise the execution, arguing that First Amendment press freedom entitles the station to do so. Prison officials counter that the regulations prohibiting the media from filming execution don’t violate the Constitution because the media “has no right of access to an execution because the state does not afford the public the right to witness an execution.”

Robert Alton Harris

In the summer of 1994, proponents of KQED’s position argued that, even though the station’s proposal might seem shocking, even barbaric, televising the execution would test the premise that the death penalty deters crime. At the very least, they argued, it would bring about a much-needed national debate and help evaluate the morality of state-sanctioned killing.

Opponents maintained that broadcasting the execution would only reaffirm what was already known—that an execution is “a grim proceeding.” Televising the event would give capital punishment opponents an opportunity to garner sympathy for the criminal, while leaving their long-dead victims silent. As one observer noted: “(T)he terrible acts of brutality committed by the individual sentenced to death will not be broadcast on a split screen along with the execution. The victim will not receive equal time. An execution is not a media event or photo opportunity.”

Ultimately, the courts ruled against KQED, determining that barring cameras at executions was a “reasonable and lawful” limit on the media’s First Amendment rights and that constraining press access was “valid and necessary” to guarantee the safety of prison personnel involved in the execution. Reporters would still be permitted to witness executions and write about what they saw. In essence, the courts concluded that allowing the media to televise executions would not “increase the effectiveness” of the reporting, but rather only “sensationalize the death of a criminal.”

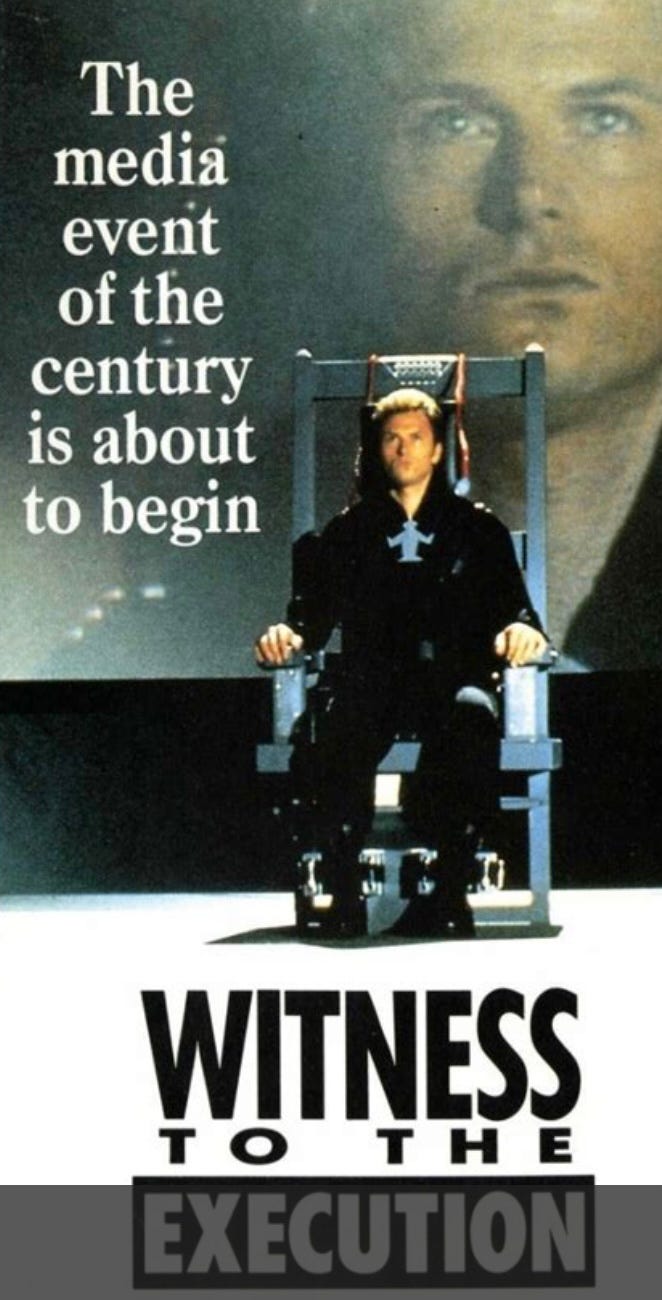

The KQED decision seemed to settle the issue, at least in California, but just three years later televised execution was again in the news. First, NBC broadcast Witness to the Execution, a fictionalized account of an electric chair execution aired over an imaginary pay-per-view TV network. A review summarized the plot: “Tycom Communications, the pay-per-view conglomerate desperate for a hit, is led by folks much like the ruthless moguls of the theatrical movie Network steeled to feverishly rationalize and defend their decision to telecast programmed death. The execs are giving part of the money to the state to help fight crime, which is how they win government approval; another portion will go to the killer’s surviving daughter, the offspring of rape.”

(Note: Paddy Chayefsky’s 1976 film, “Network,” both lampooned and eerily predicted the future of network television, with the encroachment of “infotainment” into network news divisions. It’s widely considered one of the greatest movies ever made. The film garnered 10 Academy Award nominations and won four, including Best Original Screenplay for Chayefsky, Best Supporting Actress for Beatrice Straight, and Best Actress for Faye Dunaway. Peter Finch won the Best Actor award for his portrayal of increasingly deranged news anchor, Howard Beale. As he slips into madness, Beale becomes a national sensation with soaring ratings. His impassioned catchphrase, exhorting his viewers to throw open their windows and shout, “I’m mad as Hell and I’m not going take it anymore,” is one of the best-known lines in movie history.)

Considered the most controversial made-for-TV movie of the season, Witness to the Execution was not universally acclaimed. The film got decidedly mixed reviews. Some found in shocking and thought-provoking, others considered it little more than a campy exploitation flick. North Dakota Senator Kent Conrad chastised it for being violent and opportunistic, even though he hadn’t seen it. Much of the sometimes heated discussion focused not on the issue of capital punishment, but rather on the increasing level of fictionalized, televised violence.

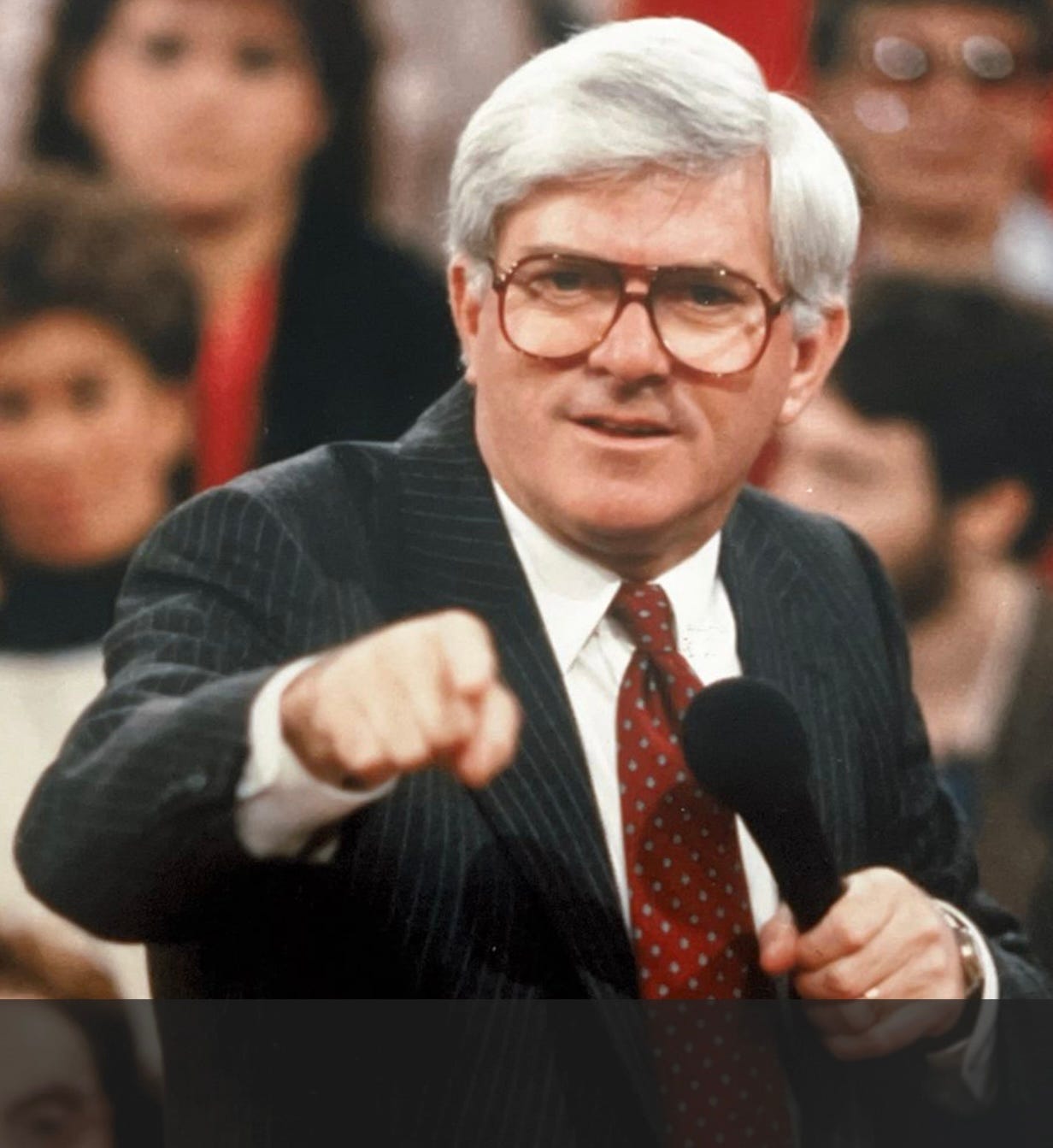

Then came Phil Donohue. Donohue was a pioneer of daytime talk shows. The Phil Donahue Show aired for almost 30 years and often tackled divisive issues. In 1994, Donahue, a death penalty opponent, sued for the right to air the execution of North Carolina death row inmate, David Lawson. Lawson had agreed to participate in the event, saying televising his execution would give his life meaning. Convicted of a 1980 murder, Lawson argued that criminals aren’t deterred by the threat of execution. He maintained that the broadcast would draw attention to the issue of untreated depression. Lawson said he had unknowingly suffered from undiagnosed severe depression most of his life and didn’t get medical help until he was on Death Row.

Talk Show Host Phil Donahue

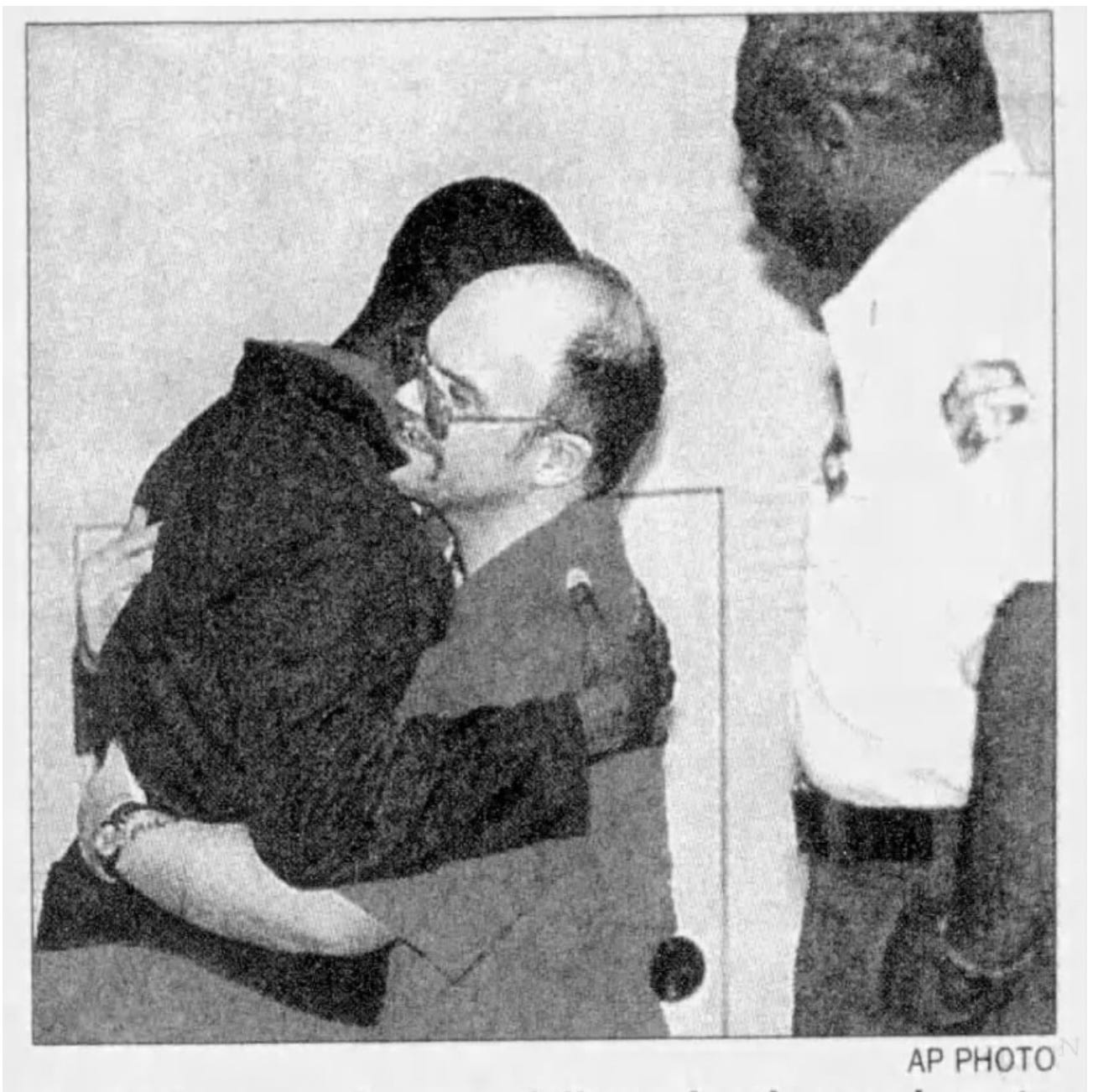

Dave Lawson, hugging a fellow Death Row inmate, the day of his execution.

“I am a human being and not a monster,” Lawson said on NBC’s Today show, shortly before his scheduled execution.

But as with the KQED case, the courts denied Donahue’s request, citing the disruption broadcasting the killing would cause. On May 18, 1994, the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled against Donahue and Lawson, saying neither the state nor the U.S. Constitution gave Donahue the right to tape the execution.

“This wasn’t a question about the constitution,” said North Carolina Attorney General Mike Easley. “This was a question about television ratings, and the state ought not to be in the business of affecting television ratings.” Easley later went on to become governor of the state.

On June 14, 1994, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the North Carolina court’s ruling, without comment. The High Court also denied Lawson’s separate request for a stay of execution. Lawson had argued that death in the prison gas chamber constituted cruel and unusual punishment. He was executed the next day.

Unsettling Settled Law

The courts’ consistent rulings that the government can limit press access to executions appear to settle the matter of televised death. But a 1992 Washington University Law Quarterly review of the various court decisions argues that public executions in the United States were stopped only because public attitudes toward the spectacle changed, and that legislatures can reverse their decisions if public attitudes change again.

The court rulings have consistently concluded that the media’s First Amendment rights have not been violated because the public’s right to view the executions is also limited. When Kentucky state legislators were embarrassed by the carnival atmosphere of Rainey Bethea’s hanging they changed the law and moved executions behind prison walls, limiting public access. They can change them back.

Although the law review article, Death TV: Media Access to Executions Under the First Amendment, concludes that the courts have ruled correctly, it also argues that the courts have “incorrectly analyzed the subject.”

“(T)elevising executions will transform private executions back into public executions,” the review argues. “The decisional law relating to press access and the right to gather information illustrates that courts cannot make this transformation under the guise of providing for effective reporting without stretching the First Amendment beyond appropriate scope. Only state legislatures, motivated by public opinion, have the power to catapult executions back into the public arena. Because an execution is not dignified or aesthetically pleasing, legislators ultimately will have to decide whether they want this type of ‘program’ to appear on American television.”

Could Florida, or any other state, revive the centuries-old practice of public executions, using the latest media technologies? The Florida legislature has already toyed with the idea.

In 1991, the Corrections Committee of the Florida House of Representatives surveyed 270 people, including about 100 Death Row inmates, on the issue. The survey was done “just out of curiosity,” a legislative aide said, and no implementing legislation was proposed. The inmates overwhelmingly supported the idea. Other respondents, including officials from the Department of Corrections, opposed it.

Support for the death penalty is strong in the Florida legislature. Just last week, a new law went into effect there expanding the methods that can be used to execute a prisoner. Prior to the change, the electric chair and lethal injection were the only methods available. But concerned that the drugs used in the injections are increasingly difficult to obtain, the legislature expanded those options to include anything “not deemed unconstitutional.” Given the new law’s broad language, Florida could join states like Mississippi, Idaho, Utah and South Carolina which include a firing squad as an execution option, or New Hampshire and Tennessee, which permit hanging.

For more than three decades, the courts have held the line against high-tech public executions. But if a willing warden, compliant courts, and supportive state legislatures deems it appropriate, in light of changing public attitudes, a live execution could soon be as close as the screen in the palm of your hand. The issue isn’t settled. Stay tuned.

Notes:

“Big Throng See Negro Die,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, August 15, 1936, p 1.

“Carnival Spirit In Kentucky Town as Negro Executed,” The Springfield (Mo.) News-Leader, August 15, 1936, p 4.

“Ozark Hill Folks Jam Courtyard for Red Jackson Hanging,” The Daily Courier (Connellsville, Pa.), May 22, 1937, p 7.

https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/history-lynching-america

https://legacysites.eji.org

Ann Norman, “Must We Share Part of the Guilt?”, The Los Angeles Times, June 4, 1955, p 15.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_Want_to_Live!

Richard Moran, “Let’s See if Barbarism Truly Deters,” The Los Angeles Times, May 1, 1991, p 324.

Harriett Salerno, “The Victim Will Not Get Equal Time,” The Los Anglese Times, May 1, 1991, p 324.

Eric Gerber, “Locally filmed ‘Witness to the Execution’ hopes to raise issues with macabre premise,” The Houston Post, February 9, 1994, p. 47.

Martin Kidman, “NBC Satirizes Its Own In ‘Witness to the Execution’,” Newsday (Suffolk Edition), February 10, 1994, p 97.

Frazier Moore, “NBC’s ‘Witness ids scorned—by those who haven’t witnessed it.” The Casper (Wyoming) Star-Tribune, January 30, 1994, p 44.

Mark Curriden, “What if executions were TELEVISED?” The Atlanta Constitution, July 31, 1994, p 181.

“Court rejects Donahue’s effort to show execution,” The Bangor (Maine) Daily News, May 18, 1994, p. 3.

Dane A. Drobny, “Death TV: Media Access to Executions Under the First Amendment,” https://journals.library.wustl.edu/lawreview/article/5180/galley/22013

“Panel to survey opinions on televised executions,” South Florida Sun Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, Florida), July 10, 1991, p. 9

“New execution methods may soon come to Florida. Here’s why.” https://www.clickorlando.com/news/florida/2025/06/28/new-execution-methods-may-soon-come-to-florida-heres-why