Murders Mount

As Osage oil revenue rose so did the number of mysterious Osage deaths. When local authorities did little to solve the cases, Osage families hired private investigators, but they uncovered only circumstantial evidence. Locals—both white and Osage—were fearful and tight-lipped. Some frightened Osage even started hanging strings of electric lights around the exterior of the homes, illuminating them throughout the night, hoping to ward off an attack.

By March 1923, an increasingly alarmed Osage Tribal Council sent a contingent to Washington, D.C. asking for federal government help. The following month, the nascent FBI sent agents to Pawhuska.

Newspapers dubbed the unsolved killing spree the “Osage Reign of Terror.” The number of tribal members murdered during the 1920s remains widely debated, but many estimate there were dozens of victims. Almost all of the killings remain unsolved.

The Murder of Anna Brown & Mysterious Death of Mollie Q

Anna Brown was murdered on May 22, 1921. About a week later, hunters found her body, decomposing and swollen almost to the point of bursting, in a field about three miles northeast of the town of Fairfax. At the site, while doctors were preparing the body for burial, the skin of the scalp slipped and disclosed a small bullet hole in the back of her head. Given the size of the hole, the doctors surmised that the murderer probably used a .32 caliber handgun. Searching for the bullet during a crude, hurried autopsy, the doctors sawed Anna’s skull in half, from front to back, removed her brain and poked sticks into it searching for the bullet. The bullet--key evidence in any murder investigation--was never found.

Anna Brown was a prime target for murder, and the first victim in a complex conspiracy to wrest a fortune from one of the wealthiest Osage families. She was a full-blooded Osage. Her mother, Lizzie Q. (also known as Lizzie Que or Lizzie Kyle) was among the wealthiest of the wealthy Indians. Controlling several inherited headrights, Lizzie Q’s fortune was said to exceed $2 million. Anna Brown and her two sisters, Mollie Burkhart and Rita Smith, were in line to inherit most of the estate when Lizzie Q. passed on.

Less than two months after Anna’s murder, 80-year-old Lizzie Q. died, apparently the victim of alcohol poisoning. With her daughter Anna dead, the bulk of Lizzie Q’s inheritance was to be divided between her two remaining daughters, Mollie and Rita.

At the time of her poisoning death, Lizzie Q was living with her daughter Mollie and her “squaw man” husband, Ernest Burkhart. In all likelihood, Ernest was slowly poisoning his mother-in-law and his wife with tainted bootleg whiskey. When Ernest was arrested and jailed for a separate crime, Mollie Burkhart started recovering from the mysterious ailment that had been afflicting her.

Ernest Burkhart was William King Hale’s nephew. He and his brother, Byron, had lived with Hale since they were teenagers. He was a father figure and they were devoted and obedient surrogate sons.

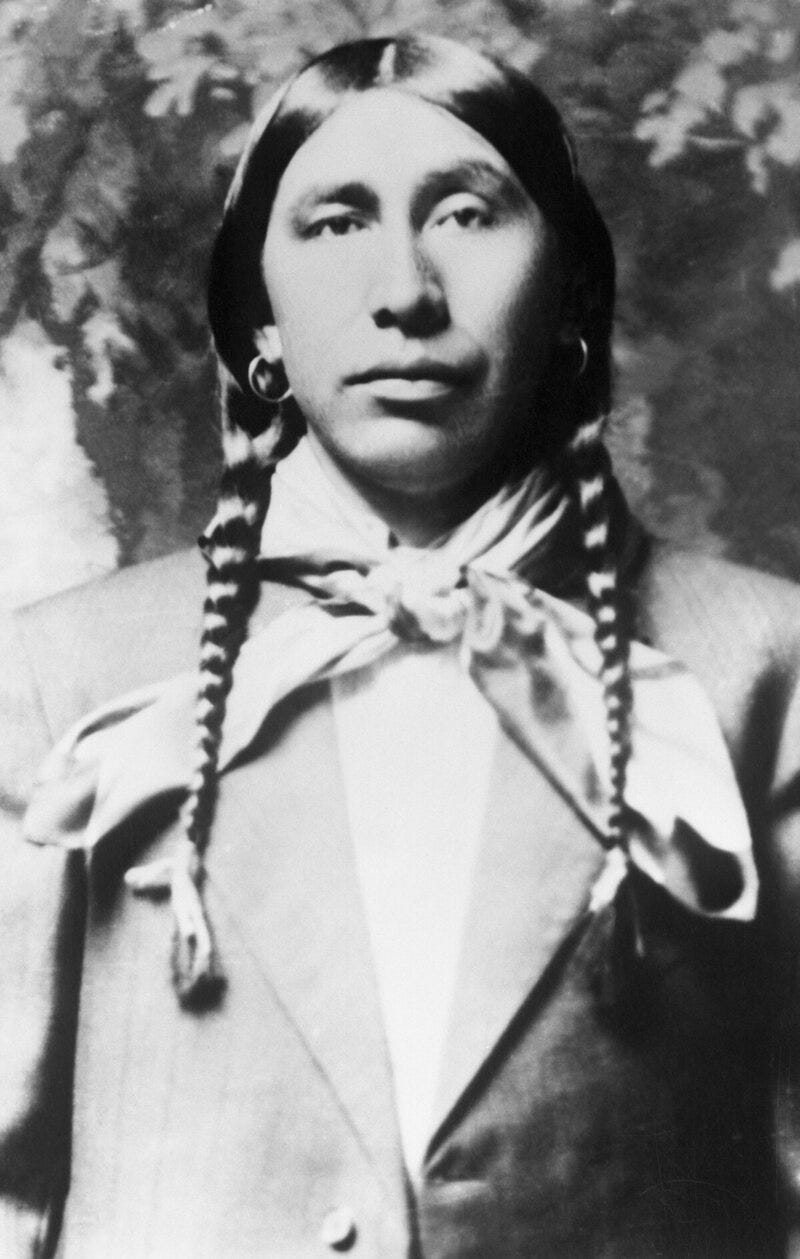

The Murder of Henry Roan

About 18 months after Lizzie Q’s demise, Osage full-blood Henry Roan was murdered. Roan was cousin to Lizzie Q’s daughters, Anna Brown and Mollie. More importantly, Roan and Mollie were said to be on intimate terms and she was talking about divorcing Ernest to marry Roan.

But a divorce between Mollie and Ernest Burkhart would have thrown as wrench into the scheme to get control of the late Lizzie Q’s vast fortune, so Hale set into motion plans to eliminate the complication by eliminating Roan and, as a bonus, make a tidy sum off of Roan’s death, as well.

In the years before his untimely death, Roan was a profoundly troubled man. He drank and spent excessively. Despite his new-found oil wealth, Roan was often in debt and despair. He had twice attempted suicide

Hale knew Roan well. He frequently loaned him spending money or more substantial sums for cattle purchases. In court testimony given after Roan’s murder, Hale said he was aware of Roan’s suicide attempts but kept loaning him money because he felt sorry for him. But as Roan’s indebtedness grew, Hale testified, he became concerned that Roan would kill himself while still owing him money. To protect against that eventuality, Hale claimed, he went hunting for a $25,000 insurance policy on Roan’s life.

Hale first approached the Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York, but that company rebuffed him, citing Roan’s previous attempted suicide. Hale then contacted the Capitol Life Insurance Company of Denver, which granted the policy, but only after Hale provided evidence to prove Roan owed him a substantial amount of money—in essence, justification for the policy. Hale produced a promissory note, drawn up in the law office of his personal attorneys, Grinstead, Scott, Hamilton, and Gross, that purported to establish Roan’s debt.

The life insurance policy on Henry Roan was issued on January 24, 1921 with Hale the sole beneficiary. But it included an important caveat. Still skittish about insuring against the life of the troubled Roan, the company’s policy stipulated that any claim filed to collect could be contested if Roan killed himself within one year of the issuance date. After that, the policy would be incontestable.

Hale paid the policy’s premiums, biding his time and launching another search—this one for Roan’s assassin. With nephew Ernest in tow, Hale called upon his longtime pal and business associate, Henry Grammer. Once a rodeo roping star and then a notorious bootlegger, Grammer controlled much of the illegal alcohol trade in north-central Oklahoma. His ranch was commonly known to be a safe haven for outlaws. Grammer recommended ranch hand John Ramsey as a man who could do the job and keep his mouth shut. Hale agreed.

“Ramsey could either give (Roan) some poison whiskey or shoot him and lay a gun beside him and everybody would think he committed suicide,” Ernest Burkhart later testified.

Per Hale’s instructions, Ramsey befriended Roan, drank with him, and sold him whiskey. Several times they met out in the country to drink. Ramsey intended to kill him each time, but hesitated. “I was trying to rib up a little more courage,” he later told federal investigators. “Finally, one day, I decided to pull the job, everything being favorable.”

The bullet entered the back of Roan’s head a little above and behind his left ear, tore through his brain, exited just above his right eye, and continued on, shattering part of his four-passenger Buick touring car’s extra heavy plate glass windshield.

Roan’s frozen body was found on February 6, 1923. He had been dead for about two weeks—a date almost exactly two years after Hale’s insurance policy on Roan was issued. A spell of relatively cold weather slowed his body’s decay. Tire tracks showed that the Buick had been driven off the main road, down an old trail and into a small canyon, about four miles from Fairfax. The pistol shot had forced Roan’s body down onto the passenger’s side of the front seat and out of view, his head resting against the seat cushion.

Had Ramsey carried out the crime as planned, Hale’s scheme to both eliminate the complication and collect the insurance might have paid off. But Ramsey couldn’t “rib up” the courage to shoot Roan face-to-face, so he ambushed him. The fatal shot to the back of the head was an illogical, if not impossible, suicide method.

Ramsey made another crucial mistake. The bit of isolated pastureland on which he killed Roan was in Indian Territory and therefore under the Interior Department’s purview. By shooting Roan there, Ramsey handed the federal government jurisdiction to bring murder charges. But it would be years before charges were filed.