Grandfather Hamilton & the Osage Reign of Terror (Part 7 & Post Script)

Family Lore & Hard Facts

Federal Charges

By late July, with the Supreme Court decision having finally settled the jurisdiction issue, Hale and Ramsey were arraigned in federal court in Pawhuska for the murder of Henry Roan. After four weeks of testimony, five days of deliberation, and 64 ballots, the foreman announced that the jury was deadlocked.

A bitter federal district attorney, Roy St. Lewis, claimed jury bias. “There are some good men on the jury and I am inclined to think there are some not so good,” he told reporters. “I have heard whisperings from Oklahoma City and Tulsa. Usually I disregard them, but I am inclined to think there are some friends of Hale’s on this jury.”

Hamilton countered that St. Lewis’s complaint amounted to, “the reward offered by a disappointed attorney to an honest jury.”

The federal prosecutors immediately moved to retry Hale and Ramsey. A new trial was launched in Oklahoma City—a venue the federal prosecutors considered less “friendly” to Hale. There, after more procedural maneuvers and courtroom shenanigans, they were convicted.

Within days, Hale and Ramsey appealed the jury’s verdict, arguing that they should have received separate trials. The Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in their favor. Retried separately, the two were again convicted. In 1929 they were sentenced to 99-year terms at Leavenworth.

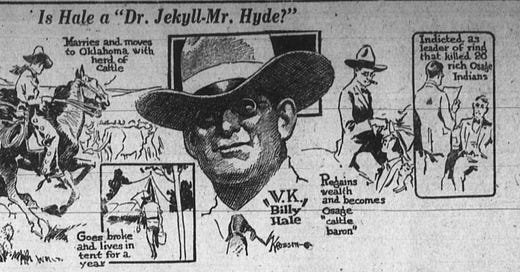

Hale’s History, from the June 16, 1926 Mattoon, Ill. Journal Gazette

What Did He Know, and When Did He Know It?

During Congressional hearings into the Watergate scandal of the 1970s, Sen. Howard Baker (R-Tenn.), the ranking minority member of the Senate Committee, summed up the essence of the inquiry with this well-known phrase: “What did the President know and when did he know it?” I think the same can be asked of Hamilton and his defense of the Osage murderers.

It is apparent that Hamilton led the effort to discredit the Bureau agents. Did the agents pressure confessions from Ramsey and Burkhart? Probably. They certainly deprived both of sleep and made vague promises of “help” or leniency. They might have pulled guns. But the elaborate stories of electric shocks, death threats and hushed, sinister conversations--to which Hale, Ramsey, and Burkhart all testified in court--were virtually identical and ring hollow. Hamilton was at the center of the smearing scheme.

J. Edgar Hoover, his agents, and the state and federal attorneys made a lot of noise about going after Hamilton and the other Hale lawyers. Hoover was “outraged” that his agents’ integrity had been questioned. He urged vigorous pursuit of whoever had sullied the court proceedings through intimidation, perjury, and jury tampering. The agents launched a months-long probe of wrong-doing by Hale’s lawyers, rounding up 65 witnesses, and presenting evidence to a grand jury. But in the end, they couldn’t prove much of anything and the allegations against the attorneys just faded away.

A few jurors were convicted of lying about their relationship with Hale when they were being vetted for inclusion on the jury. Hamilton was never charged. Only one lawyer, a junior partner of the Hale/Ramsey team, was convicted of anything—intimidating and trying to bribe witnesses.

Why did Hamilton work so diligently for so many years to clear Hale? Perhaps he honestly believed Hale was innocent or was being framed by jealous businessmen he had bested. Maybe he was concerned cold-blooded Hale would turn his anger against his attorneys or their families. Perhaps he simply thought that his client, like all clients, was entitled to the best defense possible, no questions asked.

Whatever his rationale, Hamilton skirted the subornation of perjury. He coached witnesses. He may not have blood on his hands, but they weren’t clean.

Perhaps the most damning evidence against Hamilton is what he didn’t say in his memoirs. A sprawling, three-year battle for the life of his most prominent client, covered by numerous newspapers nationwide and captured on newsreels, with a cast including cold-blooded killers and nationally known lawyers, certainly warrants more than the 30-odd words Hamilton gave it. The biggest case of his career leading to his only Supreme Court appearance—the pinnacle of a long, distinguished life in the law, seems worthy of more detail.

Post Script

Kelsey Morrison: In 1931, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals ordered Morrison’s conviction for murdering Anna Brown dismissed. The court said government prosecutors had promised Morrison immunity in exchange for information used to convict Ernest Burkhart for the Smith “blow up” murders. Morrison’s testimony wasn’t supposed to be used against him in the Brown case, but it was. Who represented Morrison on appeal? The law firm of Hamilton, Gross, and Howard.

But Morrison’s victory was, relatively and literally, short-lived. In May of 1937, the 40-year-old lifetime criminal was shot to death during a drunken gun battle with two Fairfax, Oklahoma policemen.

Byron Burkhart: Ernest Burkhart’s younger brother, Byron, was Morrison’s accomplice in the Anna Brown murder, but he got off scot-free. Morrison confessed to pulling the trigger, but claimed Byron had held up the drunken Brown so he could shoot her in the head. At Anna Brown’s inquest, Byron Burkhart swore he had driven Anna to her home in the afternoon of May 21—the day before her murder—and had not seen her after that. But numerous witnesses who knew both Byron and Anna well told investigators they had seen the two together late that evening and early on the 22nd. Caught in his lie, Byron turned state’s evidence and got immunity. Just a few months after Anna’s murder, Byron married another Osage woman. He died in 1985.

Anna Brown might have been pregnant with Byron Burkhart’s child when she was murdered. Witnesses interviewed by the Bureau agents said Anna claimed to be pregnant, named him as the father and had threatened to kill him unless he married her. Several witnesses told investigators that Byron said he’d “beat her to it.” He did. Anna had also named other men as the child’s father, including Bill Hale.

Agent in Charge Thomas B. White: The lead investigator and frequent correspondent with Hoover throughout the probes ended up with Hale and Ramsey at Leavenworth, not as a fellow inmate but as the warden. He got the job in late 1926, while the court cases were still winding their way through the judicial system. White’s Leavenworth tenure was rocky, marked by riots and jail breaks. In 1931, six heavily armed inmates stormed White’s office, shot him in the arm, took him prisoner, and fled leading to a days-long manhunt involving hundreds of guards and soldiers from nearby Fort Leavenworth. All were recaptured. White recovered and went on to head the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles.

S.P. Freeling and J.I. Howard: Hale’s 1920s legal team had star power akin to O.J. Simpson’s famous 1990s “Dream Team.” Hamilton’s firm was already well-known, but just a few weeks before the trials got underway, two more legal heavyweights signed on: S.P. Freeling and J.I. Howard.

Freeling and Howard had known each other for years. Freeling was Oklahoma’s Attorney General from 1914 to 1922 and Howard was an assistant AG. Freeling is best remembered for three things: heading the state’s “inquiry” into the infamous and bloody 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma race massacre; arguing a case before the U.S. Supreme Court which ended a long-simmering border dispute between Oklahoma and Texas; and being the driving force behind a desperate attempt to rescind the Oklahoma legislature’s approval of women’s suffrage.

Howard, who worked hand-in-hand with Hamilton trying to persuade Ernest Burkhart not to testify for the state, later became Hamilton’s law partner.

Ernest Burkhart: The government’s star witness was paroled in 1937, having served just 11 of the 99 years to which he was sentenced. Just four years later, he was in trouble again. Burkhart and Clara Mae Goad—described by the prosecutor as a “fat farm woman” and Burkhart’s “sweet patootie”—were convicted of stealing $7,000 in valuables. The victim of Ernest and Clara Mae’s thievery? Lillie Burkhart, his brother Byron’s new wife. Having violated terms of his parole, Burkhart was supposed to go to prison for the rest of his life, but he was again paroled in 1959. Six years later, Oklahoma Gov. Henry Bellmon gave Burkhart a full pardon.

J. Edgar Hoover: Hoover was FBI director for nearly 50 years. Under his leadership, the Bureau grew into a powerful, well-funded, influential crime-fighting machine. It also routinely overstepped its authority, spied on and harassed political dissidents, and violated civil rights. Like Bill Hale, Hoover was loved, hated, and feared. When he died in 1972 the FBI’s seamier side was still largely unknown so Hoover was generally revered. His body lay in state in the Capitol Rotunda, an honor usually reserved for presidents, prominent members of Congress, and military heroes.

William King Hale: Hale never collected on the $25,000 life insurance policy he had taken out on Henry Roan. Investigators for the life insurance company found that Roan hadn’t been truthful in the application. He failed to mention that he had been rejected for the earlier policy and apparently didn’t disclose that he had venereal disease and tuberculosis, so the policy was obtained fraudulently. Hale sued to recover the $25,000, but lost.

Even if all of his devious plans had worked out, Hale also wouldn’t have gotten the Smith family’s part of the Lizzie Q fortune. Bill Smith knew Hale was gunning for him, so he and his wife changed their wills. Smith had a daughter from a previous marriage. He left the bulk of the estate—including the valuable headrights—to her.

If Hale had managed to beat all of the charges against him, he apparently would have had his disloyal nephew Ernest killed. While in jail in Pawhuska awaiting trial, Hale solicited another assassin. According to a cellmate, Hale planned to have friends smuggle guns into the jail so the killer could escape and then, to return the favor, kill Burkhart.

Was Hale a psychopath? Professional psychiatric journals and reference materials describe psychopaths as individuals who lack emotions such as shame, guilt, and embarrassment. They are notorious for their lack of fear. They blame others for events that are their fault and while they might admit blame when cornered, they do so without any sense of shame or remorse.

Psychopaths are described as “glib” or superficially “charming.” People who fall into the general category of personality disorders that include psychopathy often con others “for personal profit or pleasure.” They have a “grandiose sense of self-worth” and can be pathologically egocentric, and violent.

An August, 1941 psychiatric evaluation of Hale, conducted at Leavenworth as part of a routine “Parole Progress Report,” reads like a textbook psychopath’s profile. During the evaluation, Hale was “jovial, pleasant, and agreeable.” He said he wasn’t applying for parole at that time, believing it wouldn’t be granted. But he added that “influential people” were working to get him released.

“He admits that he has more faith in political ‘pull’ and influence than he has in applying through the regular channels,” the report says. “This naïve faith in political influence has characterized him ever since he has been here, and it is evidence of his extremely poor judgment and of his distorted manner of thinking.

“His poor judgment is further evidenced by his continuing denial of his obvious guilt,” the report continues. “He still claims that he should never have been sent here and was convicted wrongly, and he talks cheerfully about this and without emotion. He does not appear to have suffered any intellectual deterioration since he has been confined in this institution, but he has put behind him any feeling of shame or repentance he may have had, and he continues to stress his innocence and probable release through influence of friends. It is obvious that this man has suppressed the facts of the instant offense to the background of his mind and no amount of probing will enable us to get in touch with his true feelings.”

Psychopath or not, Hale was a well-behaved prisoner. Despite strenuous objections from Osage leaders and FBI Director Hoover, Hale was paroled in 1947, having served 18 years of his life sentence. Under terms of his release, the 72-year-old Hale was supposed to live with his daughter in Wichita, Kansas, but that arrangement lasted less than two years. In April of 1949, Hale was again associating with the two things he knew best: cows and criminals. He headed west to Montana to raise cattle on a ranch owned by longtime family friend and fellow-Texan, Bennie Binion. Binion was a bootlegger, bookmaker and convicted murderer. Like Hale, he was flamboyant, well-liked, well-connected, and vicious.

Hale died in Phoenix on August 15, 1962. He’s buried at the Old Shawnee Mission Cemetery.

William Slaughter Hamilton: W.S. Hamilton had a long and distinguished legal career and was an active member of the community. He was the attorney for many local institutions, including a savings and loan. He was city attorney for both Pawhuska and Nowata and for various school districts in the state.

He headed both the Osage County and Oklahoma State Bar Associations and led Oklahoma’s effort to raise money for construction of the American Bar Association’s Law Center in Chicago. In 1964, when his alma mater, Valparaiso University, dedicated a new law school building, Hamilton was among four recipients of honorary doctorates. The other three were Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren, and a federal appeals court judge. Pretty rarified company for a self-described “country lawyer” from Pawhuska.

Hamilton lived in Pawhuska, in the same $6,000 house he had bought in the ‘20s, until his wife, Mabel, died on August 21, 1968, two weeks after their 65th wedding anniversary. He moved to Des Moines, Iowa to live with his youngest daughter, Elizabeth. He died on November 1, 1969. He and Mabel are interred in a mausoleum in Pawhuska City Cemetery.