The Murder(s) of a North Carolina Enslaver

This is a story—well, two stories, actually—about the murder of a North Carolina enslaver.

It’s a story of family lore and unvarnished historical truths; of diabolical evil, heroic persistence, unending heartlessness, and enduring love; of desperation, gruesome acts and, ultimately, futility and injustice.

The family lore comes from an August 6, 1937 interview of Dave Lawson, the grandson of the enslaved people who committed the crime. “This isn’t a nice tale you’re going to hear,” Lawson told Work Progress Administration (WPA) interviewer Travis Jordon. “It’s the truth, but it isn’t nice.”

Lawson’s conversation with Jordan was part of a WPA program aimed at gathering the stories of formerly enslaved people. Lawson himself had never been enslaved and the recollections he shared were based on what older relatives had told him.

Lawson said his grandparents—Cleve and Lissa—were owned by Drew Norwood, a wealthy North Carolina planter and slave trader. When Norwood bought the couple, he did not purchase their infant daughter, Lawson’s mother. She was raised by Lissa’s sister, Lawson’s aunt, who passed down the family’s oral history.

In Lawson’s account, Norwood is the epitome of evil, a brutal heartless tyrant reminiscent of the vicious plantation owner, Simon Legree, in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

“They say my grandparents’ Old Master was the meanest man the Lord ever let breathe the breadth of life,” Lawson told Jordan. Though Norwood was one of the richest landowners in North Carolina, he made most of his money buying and selling slaves, Lawson said. “He bought them cheap and sold them high” often in the Deep South where they brought more on the auction block.

Norwood bought Cleve and Lissa for $450, Lawson said. He didn’t buy their baby girl because he feared she would die before she was old enough to sell. Lissa was devastated by the separation, but Norwood “laughed and told her he would give her a puppy from one of the hounds on his plantation” to ease the pain, Lawson added.

The Epitome of Evil

Norwood’s cruelty was boundless and he wielded his braided whip with impunity, Lawson said. The Lawson family’s oral history described him in detail. “I was told he looked like a mad bull,” Lawson said. “He was short with a big head set forward on his shoulders. The devil lit a lamp and set it burning in his eyes; his mouth was a wicked slash cut across his face, and when he got mad his lips curled back from his teeth like a mad dog’s.”

He was stunningly cruel. “Yes sir,” Lawson recounted. “Everything on that plantation, animal and man, was scared of that whip—that whip that never left Master Drew’s wrist. It was made of home-tanned leather, plaited in a round cord as big as a man’s thumb. All day it swung from the leather strap tied to his wrist and at night it lay on a chair beside his bed, where he could reach it easily.”

According to Lawson, Norwood’s cruelty extended to his own family. “He beat Mistress, too,” Lawson told the WPA interviewer. “Mistress Cary wasn’t any bigger than a minute and she was scared on Master Drew.” Once, when his wife salved the wounds of an enslaved victim of Norwood’s wrath, Norwood laid into her with the whip, even though she was pregnant with their first child.

“Mistress Cary ran and ran around the house, but Master Drew ran after her and, every now and then, threw out the plaited whip and curled it around her shoulder,” Lawson said. “Miss Cary got so scared that the baby came that night, before it was time. The baby was born dead. Mistress Cary went on to glory with it. They say she was glad to go.”

Cleve and Lissa worked hard amid the terror of plantation life, “too hard for their own good,” Lawson said. “In those days, it was the smart, hard-working slaves that brought the best prices and nobody knew that better than Master Drew.”

One day, according to the family account, Cleve saw Norwood eyeing Lissa as she gleaned wheat from the plantation fields. He had “a lustful look in his eyes,” but it wasn’t Lissa he was lusting after, it was the money she represented. “Stripped to her waist on an Alabama auction block, she could bring near about $1,000,” Lawson said.

Cleve understood what Norwood was planning. He had already taken Cleve’s baby away, and now he was going to take Lissa. He knew Norwood didn’t care if he parted the pair. “It was dollars he saw swimming around in his head—gold dollars shining brighter than the stars,” Lawson added.

The Decision to Act

Cleve was determined to stop the separation. When Norwood came to the couple’s cabin to announce his intention to sell Lissa, Cleve begged and pleaded and promised to do anything Norwood asked, but Norwood was unmoved. When Norwood left, Celeve assured Lissa they would never be separated.

“Then he told her to make up a hot fire, while he brought in a wash pot from outside,” Lawson said. “He brought in a big iron pot and set it on the hearth and raked the red hot coals all around it. Then he filled it with water. While it was heating, he went to the door and looked out. The sun had gone down and night was crowding the hills, pushing them out of sight. He knew, by daylight, that white man was coming for Lissa.

“Cleve turned around and looked at Lissa,” Lawson continued. “She was standing by the wash pot, looking down in the water and the firelight from the burning lightwood knots showed the tears dropping off her cheeks. Cleve went outside. A screech owl came and set on the cabin roof and screeched. Lissa ran out to scare it away, but Cleve caught her and said, ‘Don’t do that Lissa, leave him alone. That’s the death bird. He knows what he’s doing.’ So Lissa didn’t do anything and let the bird keep on screeching.”

When darkness fell, Cleve took a long rope and left the cabin, telling Lissa to keep the water in the pot boiling. When he came back, he had Norwood thrown over his shoulder, bound and gagged.

Cleve laid him on the cabin floor. He told Norwood that, if he promised not to sell Lissa, he wouldn’t hurt him, “but the Old Master shook his head and cussed in his throat,” Lawson recounted.

“Then Cleve took off the gag and, before that white man could holler, Cleve stuffed the spout of a funnel in his big mouth way down his throat, holding down his tongue,” Lawson continued. “He asked him one more time to save Lissa from the block, but Master Drew looked at him with hate in his eyes and shook his head again. Cleve didn’t say anything else to him; he called Lissa and told her to bring him a pitcher of the boiling water.

“By then, Lissa saw what Cleve was planning to do,” Lawson said. “She didn’t tell Cleve not to do it; she just filled the pitcher with hot water. Then she went and sat down on the floor and held Master Drew’s head so he couldn’t move.

“When Old Master saw what they were fixing to do to him, his eyes nearly busted out of his head, but when they asked him again about Lissa, he wouldn’t promise anything, so Cleve sat on him and held him down and started pouring that boiling water right into the funnel sticking out of Master Drew’s mouth.

“That man kicked and struggled, but the water scalded its way down his throat, burning up his insides. Lissa brought another pitcher full and there wasn’t any pity in her eyes as she watched Master Drew fighting his way to torment.”

After the murder, Cleve and Lissa sat down and waited for the sheriff, Lawson added. They knew there wasn’t any use in running, “because there was nowhere to go.” At sunup, neighbors came and found Norwood. They also found Cleve and Lissa, “sitting, hand in hand, waiting,” Lawson said.

Cleve and Lissa confessed. “The sheriff took the rope from around Master Drew and cut it into two pieces. He tied one rope around Cleve’s neck and one around Lissa’s and hanged them in the big oak tree in the yard.”

Lawson told the WPA interviewer that the cabin in which they sat was the same one where Cleve and Lissa murdered Norwood and that an old oak tree on a nearby path was the same tree from which his grandparents were hanged.

“Sometimes now, in the Fall of the year when I’m setting by the door after the sun has gone down; and the wheat is ripe and bending in the wind, and the moon is round and yellow like a muskmelon, seems like I see two shadows from the big limb of that tree—I see them swinging low, side by side, with their feet nearly touching the ground,” Lawson said.

Dave Lawson’s account of the Norwood murder reads like an allegory on the evils of enslavement, the bravery of the enslaved, and the bounds of human suffering. Though Lawson assured the WPA interviewer that the story was true, the family’s oral history is, in fact, an embellished account of actual events. Many of the gruesome details mirror what really happened, but other significant details do not.

“A Horrible Affair”

In late October, 1856, a prominent North Carolina merchant was found dead in his home “in a sudden and mysterious manner.” Initial accounts said he had bid his overseer good night and gone to bed around 9:00 PM. A couple of hours later, some of his enslaved people told neighbors that the merchant “had fallen in the fire and burnt to death” in his bedroom.

“The neighbors immediately assembled and found him a corpse,” the Concord (NC) Weekly Gazette reported. “Burns upon different parts of his person were discovered, but his hair was not singed even, and his clothing was without a scorch.”

“Upon these circumstances it was supposed that the burns must have been scalds from hot water,” the news account continued. “An examination being instituted, suspicion rested upon his negroes, and it is now ascertained that he was foully and shockingly murdered by two of his slaves.”

The merchant’s name was Lewis Norwood. The story of his gruesome death spread quickly, picked up by more than 50 newspapers across the U.S, Canada, and England. The Opelousas Louisiana Courier even translated it into French.

The Norwood murder came amid mounting violence between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces. Just a few months earlier abolitionist John Brown and his sons had brutally murdered pro-slavery settlers in Kansas, sparking an escalation of violence in the territory and setting the stage for southern secession and the Civil War. Fear of slave uprisings gripped enslavers throughout the south.

At a time when buying, selling, and owning other human beings was sanctioned under law and defended by a selective parsing of scripture, enslaver Lewis Norwood was described in the press as “an influential and widely known” merchant, “an estimable gentleman and good neighbor,” and “a kind humane master.”

The “diabolical outrage” against Norwood required swift punishment, pro-slavery editorials said. “It is one of the most cruel and atrocious murders that we have been called upon to record,” the Weekly Chicago Times reported, “and we sincerely trust that the fiendish perpetrators may pay the penalty of the horrid crime, by the forfeiture of their lives.”

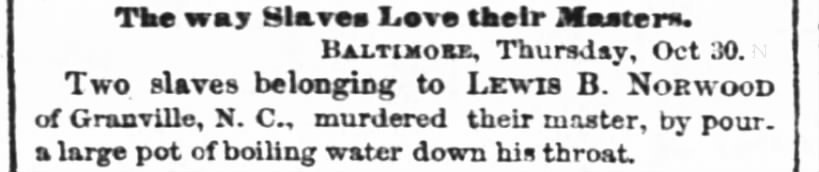

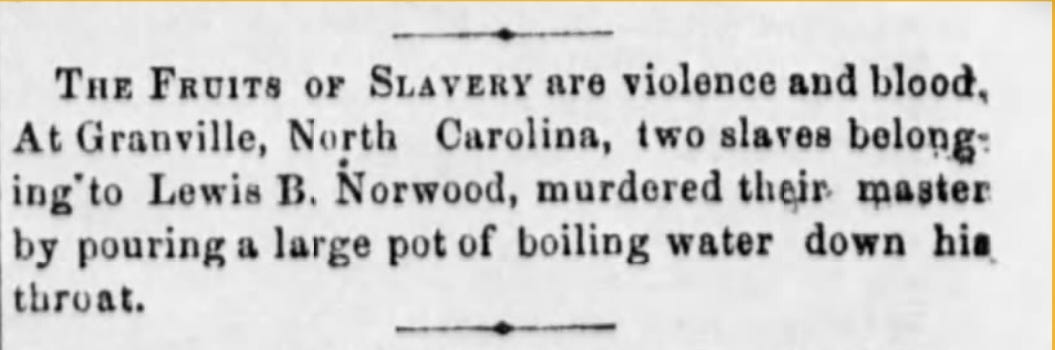

A brief item, typical of Pro-Slavery newspaper accounts

A brief item in the Anti-Slavery Bugle, an Ohio newspaper, viewed the incident differently, but most headlines spoke of the “horrible affair” and “fiendish murders.”

Item from the Anti-Slavery Bugle, November 15, 1856.

Additional details concerning Norwood’s murder soon came to light and an enslaved couple were soon in a Raleigh, N.C., jail. Their names were Joe and Massey

Contemporaneous accounts mirror much of Dave Lawson’s narrative. In the November 5, 1856 issue of the Raleigh Weekly Standard, titled “Coroner’s Inquest,” the paper wrote that on the night of the murder Norwood had gone to one of the enslaved people’s cabins looking for a key that had been misplaced.

“A woman got up and upon pretense of looking for it got behind him and immediately seized him and threw him down upon the floor,” the news account said. “A negro man then came to her assistance, and taking hold of his arms held him down. The woman in the meantime stuffed his mouth full of rags and set them on fire,” the story continued.

“Finding this would not kill him, she seized a kettle of boiling water and attempted to pour it down his throat. He was by this means badly scalded about the neck and mouth. The woman then seized a lightwood knot in the room and struck him a fatal blow.”

According to the newspaper, Norwood’s body was taken to his bedroom and placed near the fireplace. The fire was replenished and kindled into a blaze, presumably to make it look like Norwood had toppled in and burnt himself to death.

Other news accounts similarly said the perpetrators had tried to cover up their crime by taking Norwood to his bedroom and positioning his body and an empty liquor bottle near the fire in such as way as to make it appear as if a drunken Norwood had fallen in.

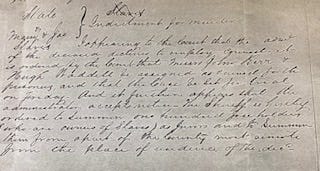

Joe and Massey were indicted for the murder. In March, 1857, they were tried in the Granville County, N.C. courthouse. They pleaded not guilty. Court-appointed attorneys defended them. The Weekly Raleigh Register reported that the couple’s attorneys were “eloquent and ingenious” in their defense. Apparently resigned to the near-certain guilty verdict from the slave-owning jurors, Joe and Massey told the court they had “nothing further to say then what they had already said” about the charges against them. The jury “of good and lawful men” pulled from a pool of 100 slave-owning citizens quickly found them guilty. They were hanged by the Granville County sheriff on the public execution grounds in Oxford on May 8, 1857.

The indictment ordering the sheriff to gather 100 potential jurors “who are owners of slaves.”

The indignities they suffered didn’t end with their deaths. In a 1915 newspaper article recounting the rare executions of women in North Carolina, the son of a local physician who witnessed the hanging as a boy, said his father, “secured one of the bodies and had the skeleton mounted, keeping it in his office for medical purposes.”

The WPA Narratives

Historians have long debated the accuracy and value of the WPA Slave Narratives for a variety of reasons. Most of the interviewers were white people, interviewing formerly enslaved people in the Jim Crow south. Most of the interviews took place in urban settings, rather than rural ones, raising questions about whether first-hand accounts of plantation life were under-represented. The age of many of those interviewed and the passage of time raise questions about the accuracy of the accounts. Yet, they have value. Even if specific details are lacking or inaccurate, they offer first-hand insights into the lives of those enslaved.

At the outset of his interview, Dave Lawson told the WPA’s Travis Jordan that the story he was about to tell him, wasn’t “a nice tale” but that it was “the truth.” There’s no reason to suspect Lawson doubted the accuracy of what he was about to say. The many similarities between the Lewis Norwood and Drew Norwood murders suggest that Lawson’s family simply incorporated the actual events into family lore.

Through Dave Lawson, Cleve and Lissa gave voice to Joe and Massey. That, in itself, seems enough.